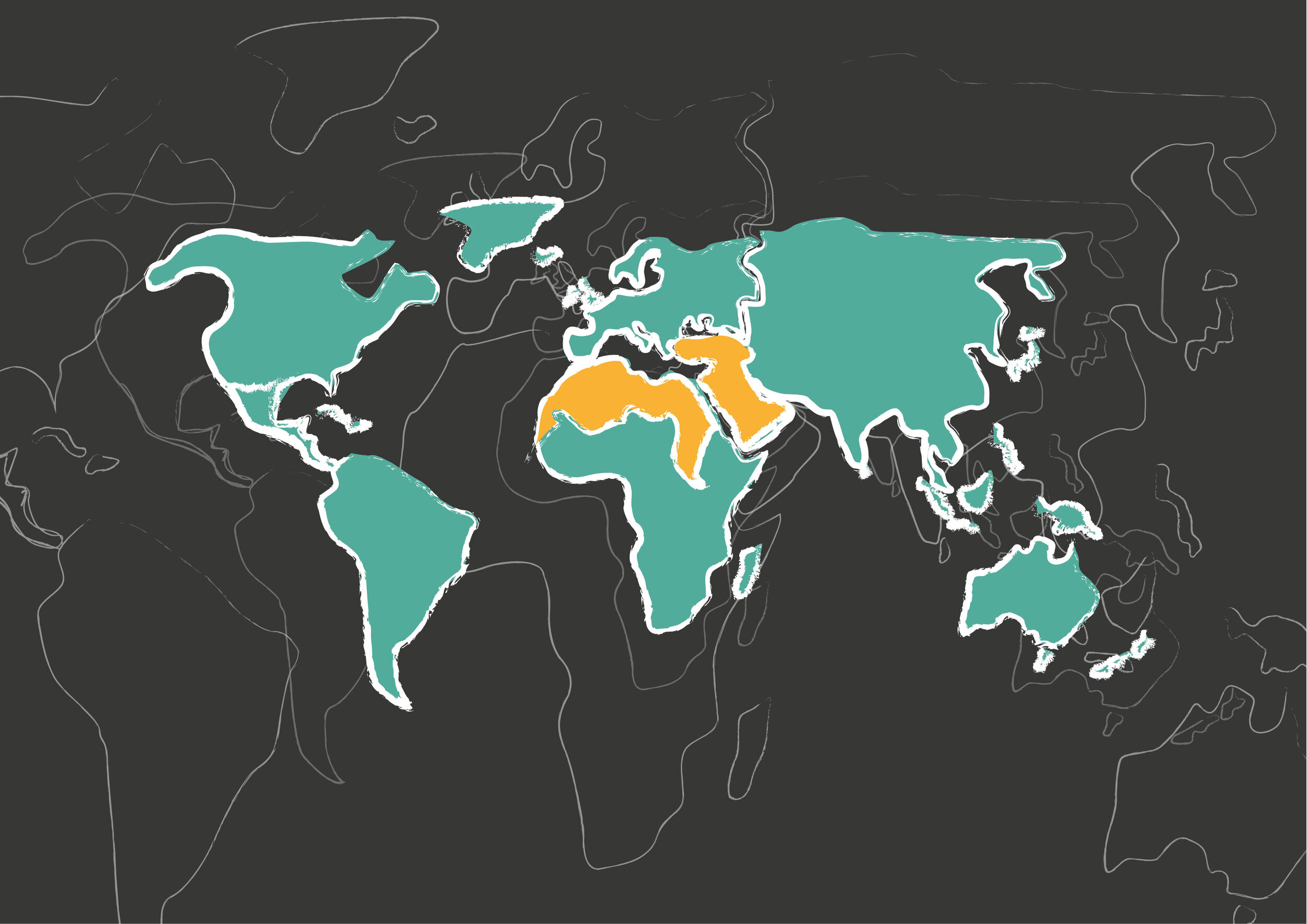

Middle East & North Africa.

Migration: European Union and Libya’s Detention Centres

Although migration has been at the forefront of European Union policy-makers’ and leaders’ minds, the current pandemic has undeniably made the above issue a much more challenging and pressing subject to deal with. In the midst of indecision over how to solve the issue, the current status quo involves the militarisation of borders and the outsourcing of border control to neighbouring nations. Specifically, the outsourcing of border control has become a particular point of contention when it comes to the treatment of migrants.

This can be acutely seen in Libya, whereby the current political instability of the country itself and other nations, has become a vessel for migration across the Mediterranean Sea towards Italy. For the European Union, one of the main objectives in dealing with Libya as a neighbouring country is to reduce the inflow of migrants towards its borders. In enforcing this objective, the European Union has invested heavily in strengthening the Libyan’s coastal and border control capacities to ensure migrant boats are intercepted and sent back to their original country.

However, there have undoubtedly been issues regarding not only the controversial objective of how we limit migration, but also the tools in which this objective is enforced. In particular, the European approach has been admittedly laissez-faire in how it aims to deal with migration. These have included instances in which migrants are currently housed in poor living conditions at detention centres, which poses multiple questions over Europe’s central principles of human rights and dignity in dealing with migrants.

Europe’s lack of willingness to deal with migration more effectively, which enabled a system of outsourcing to be constructed, can be seen to be at odds with the underlying premises of protecting human rights enshrined in EU law. This can be exemplified in Italy’s aid and assistance to the Libyan Coast Guard - the aid and assistance from Italy gives it a certain degree of culpability in the conditions of Libyan detention centres once migrants are intercepted at sea. A failure to acknowledge this trade-off, in which outsourcing the control of migrants to North African states creates implicit culpability in the EU’s actions. Whilst being inconsequential at the moment, it is bound to have unintended consequences in the long run.

Specifically, the lack of accountability that comes with this system of outsourcing, in which there is lack of jurisdiction of the implementation of EU law, will have long-term repercussions in how it deals with its internal security becoming a source of insecurity for others. The lack of oversight of detention centres, in which the EU forgo authority, opens up questions over how abuses can be put to justice when there is no one in particular that can be blamed. This has become the key issue which calls for an inquiry into how far Italy can be held responsible or negligent over the torture of migrants and refugees in Libya.

A question that is grappling many international human rights lawyers is how a lack of oversight over detention centres, in which the European Union implicitly funds, has troubling long-term consequences for those currently in detention centres that have no access or means to bringing redresses to these inconsistencies in applying refugee law.